Introduction

Biodiversity includes all components of the living world, the number and variety of native plants, animals and other living things across our land, waterways, marine and coast. It includes the variety of their genetic information, their habitats and their relationship to the ecosystems within which they live1.

Biodiversity underpins a healthy natural environment. It is fundamental to our economy, our physical and mental wellbeing and has value and a role in nature in its own right. For Traditional Owners, biodiversity has cultural and spiritual value and is part of their connection to Country.

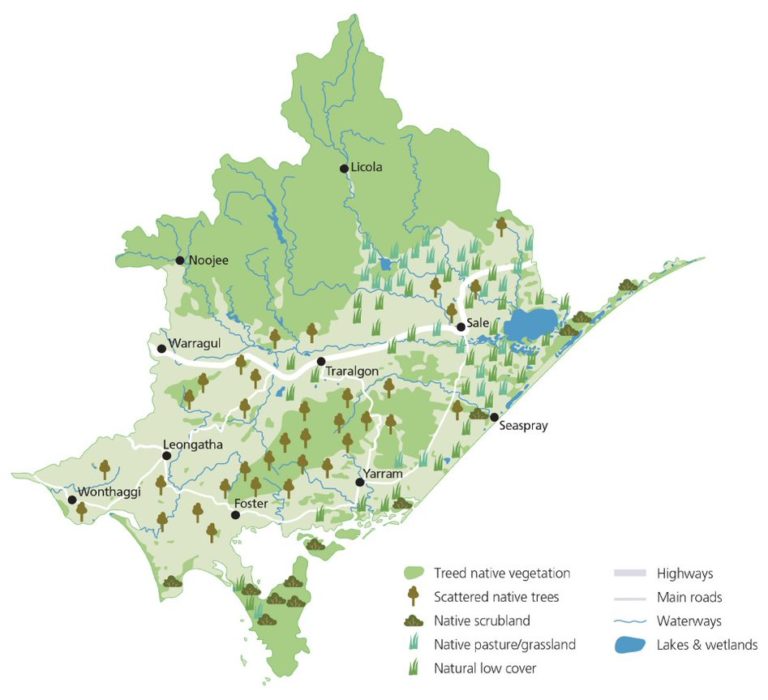

The West Gippsland region supports large areas of high biodiversity value, many of which are located within parks and conservation reserves on public land. Native forests, coastal and wetland environments, along with waterways provide important habitat and corridors for a range of flora and fauna species. These areas are a focus for active management, research and citizen science activities involving public land managers, Traditional Owners and community groups.

Remnant vegetation in cleared agricultural areas, along waterways and around towns and built-up areas are also important areas of natural habitat. Protecting and linking these through permanent protection, revegetation and enhancement activities are a focus for community based on-ground action.

West Gippsland’s unique biodiversity

The West Gippsland region has a diverse range of ecosystems, with six of Victoria’s 28 terrestrial bioregions represented in the region, including all of the Wilsons Promontory bioregion and most of the Strzelecki Ranges bioregion. The Gippsland Plain bioregion is the most extensive bioregion, and has been heavily impacted by historic clearing for agriculture, industry and settlement. The Highlands Southern Fall bioregion is the second most extensive and is mostly within public land in state forests and parks. The region also contains part of the Victorian Alps and East Gippsland Lowlands bioregions.

Four of the five Victorian marine bioregions are also represented in the West Gippsland region including:

- Central Victoria (San Remo to Cape Liptrap)

- Flinders (Wilsons Promontory to the western extent of the Ninety Mile Beach)

- Twofold Shelf (from the western extent of Ninety Mile Beach eastwards)

- Victorian embayments (bays, inlets and estuaries).

While the region is home to diverse terrestrial, marine and aquatic flora and fauna species, many of these are threatened. Over 95 fauna and flora species listed under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act) and over 600 of Victoria’s threatened species formally listed under the Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act 1988 (FFG Act) have been recorded in the region. There is also a high representation of endangered, rare and vulnerable ecological vegetation classes (EVC) across the region.

The challenge of declining biodiversity

Victoria’s biodiversity, including native flora and fauna and their habitats, has been declining since European settlement. Victoria has lost around 80 species, and between one quarter and a third of all of Victoria’s terrestrial plants, birds, reptiles, amphibians and mammals, along with numerous invertebrates and ecological communities, are considered to be at threat of extinction6. Climate change and population growth are expected to exacerbate existing threats and bring new challenges for Victoria’s biodiversity1.

Protecting Victoria’s Environment – Biodiversity 2037 and the regional Biodiversity Response Planning process

Biodiversity 2037 Protecting Victoria’s Environment is Victoria’s 20-year plan to stop the decline of native plants and animals and improve the natural environment. Biodiversity 2037 sets targets for management outputs (including weed control in priority locations) that contribute to biodiversity outcomes and the goal ‘Victoria’s natural environment is healthy’.

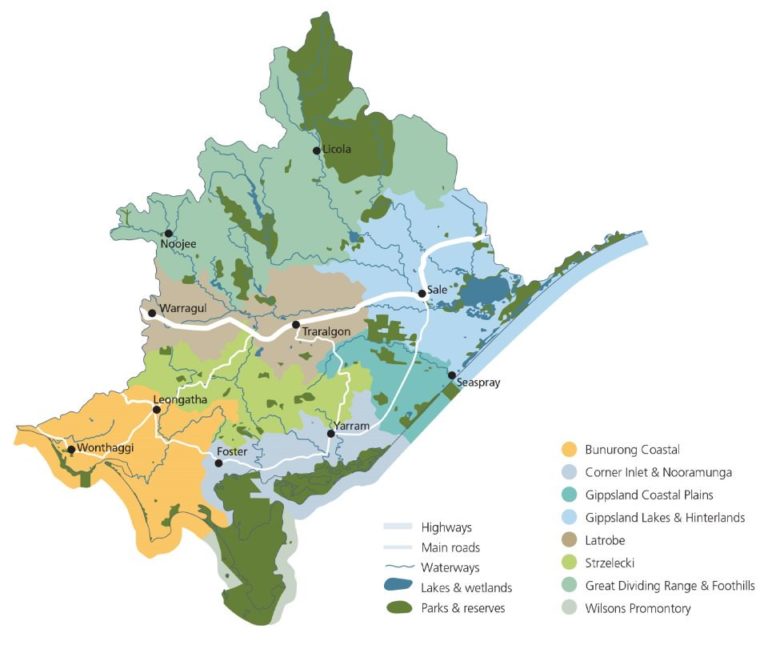

Under Biodiversity 2037, the Biodiversity Response Planning (BRP) process is a long-term area-based planning approach to biodiversity conservation. It is designed to strengthen alignment between agencies, Traditional owners and the community by working together to identify, promote and tackle local biodiversity needs as part of an ongoing collective process. The regional BRP process identifies Focus Landscapes and the priority actions for these landscapes drawing on stakeholder input, local knowledge and modelling. There are seven focus landscapes in West Gippsland region.

More information on the region’s biodiversity values and actions to protect biodiversity is available via a set of fact sheets for Biodiversity Response Planning focus landscapes. The fact sheets can be used to provide direction on what on-ground activities would be highest priority to do to get the best biodiversity result. This can be helpful when thinking about applying for funding to undertake on ground projects.

New Flora and Fauna Guarantee list

Over the past four years, the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning, has been leading a project to assess the conservation status of all Victorian threatened species. Following the gazettal of almost 2,000 species in May and June 2021, Victoria’s new Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act Threatened List is now available.

The new FFG Act Threatened List, simplifies planning and regulatory processes by creating a single list for Victorian threatened species aligned to the International Union for Conservation of Nature Assessment Method agreed by State and Commonwealth Environment Ministers and enshrined in the FFG Act.

Statewide Conservation Plan

The Trust for Nature (TfN) is currently revising its Statewide Conservation Plan. The plan will include provisional targets that aim to significantly increase the area of private land that is permanently protected with a focus on conserving under-represented ecosystems and addressing the dual threats of climate change and land clearing. The regional outcomes in this RCS will reflect and align with the provisional targets identified in the Trust for Nature new Statewide Conservation Plan and those outlined in Biodiversity 2037.

Condition and Trends

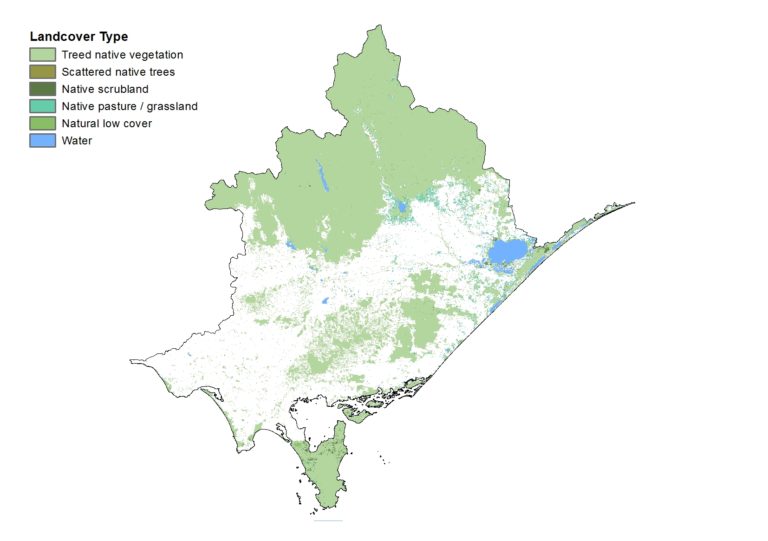

Native Vegetation Cover

An estimated 52% of West Gippsland’s pre-1750 native vegetation has been cleared. Much of the remaining 48% is located on public land in the upper catchment areas of the Great Dividing Range and eastern Strzeleckis, within Wilsons Promontory and along the coast. By comparison, native vegetation extent is classified as poor to moderate in the lower reaches of the catchments. Of these areas native vegetation is fragmented and or degraded, since it is generally located on land that had been historically cleared for agriculture, settlement and industry2.

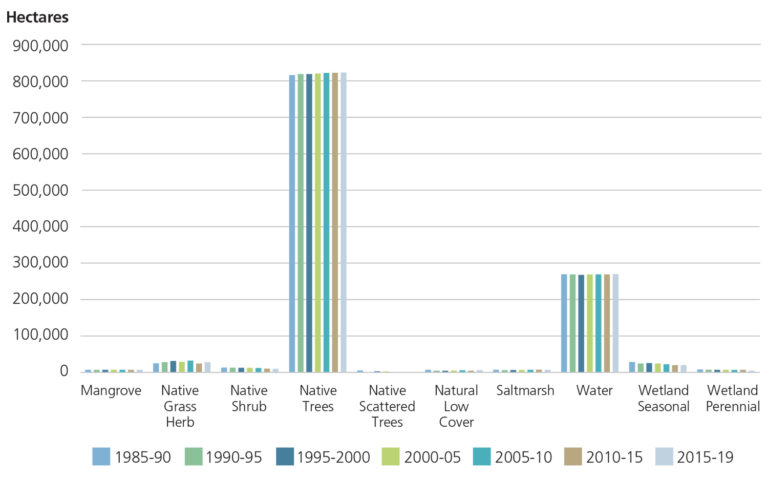

The recently released Victorian Land Cover Time Series 1985-2019, shows trends over time for different native vegetation classes2.

The data shows a decline in the hectares of native scattered trees (-53%) and native shrub cover (-21%) over the past 34 years.

Overall native tree cover is relatively stable (1%) as are native shrubs (3%). Natural low cover includes environments with naturally low to negligible vegetation such as lake beds and rocky outcrops.

Wetlands and coastal vegetation are included in the graph as a component of native vegetation (refer to the Water & Coast and Marine theme page for more information).

This data will be used by RCS partners to monitor future trends.

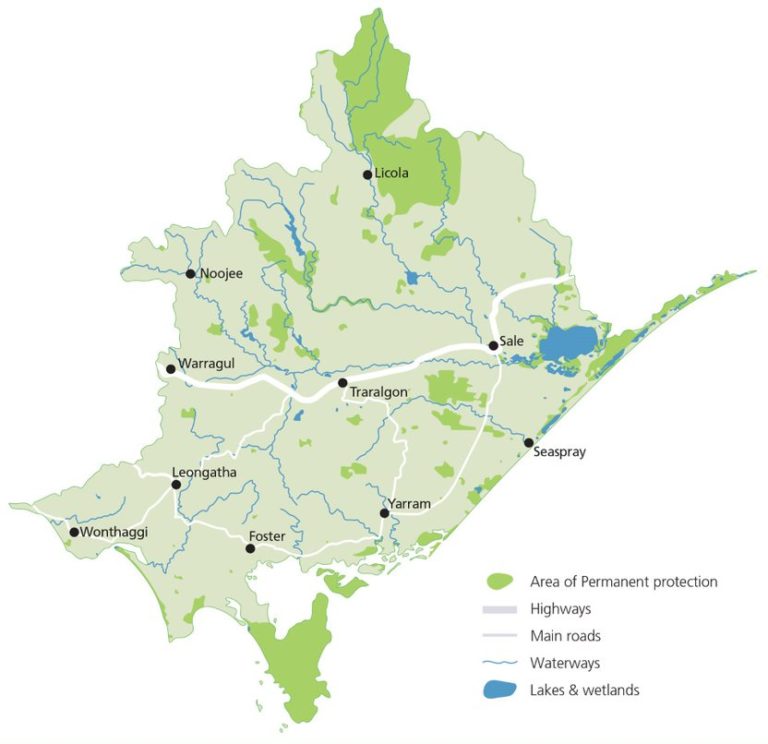

Areas of permanent protection in the West Gippsland region

Eighteen percent (18%) of the West Gippsland region is under permanent protection via the public reserve system and conservation covenants. Of this the majority is within National Park and equivalent reserves4;5.

Large areas of habitat are conserved through permanent protection in the Corner Inlet and Nooramunga, Great Dividing Range and Foothills, and Wilsons Promontory local areas. The proportion of protected areas in the Bunurong Coastal, Latrobe and Strzelecki local areas is much lower than other parts of the region.

| PROTECTION TYPE | PROPORTION OF TOTAL PROTECTED AREA (%) | TOTAL AREA | ADDITIONAL AREA (HA) SINCE 2017 |

|---|---|---|---|

| National Park | 64% | 229,687 | 0 |

| State Park | 5% | 18,101 | 0 |

| Conservation Covenant and other private lands | 2% | 7,387 | 604 |

| Other* | 29% | 104,259 | 0** |

| TOTAL | 359,299 | 604 |

Progress towards Biodiversity 2037 regional targets

The table below sets out the progress towards Biodiversity 2037 regional targets as at June 30, 2020. Progress reporting has been collated by DELWP and does not fully reflect all of the actions and projects undertaken in the region.

| TARGET DESCRIPTION | QUANTITY (HA) | PROGRESS WITHIN PRIORITY LOCATIONS (at JUNE 30,2020) | PROGRESS OUTSIDE OF PRIORITY LOCATIONS (at JUNE 30,2020) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sustained herbivore control | 220,000 | 45,493 | 16,287 |

| Sustained predator control | 150,000 | 42,662 | 32,790 |

| Sustained weed control | 50,000 | 15,547 | 6,890 |

| Revegetation (since 2017) | 10,000 | 0 | 258 |

| Permanent protection (since 2017) | 70,000 | * | * |

Herbivore, predator, weed control:

- targets = ha/year

- progress = 2019/2020 activity in priority locations reported to DELWP.

Revegetation:

- target = cumulative ha since 2017

- progress = cumulative ha 2017/18 to 2019/20 in priority locations reported to DELWP.

Permanent protection:

- target = cumulative ha since 2017.

Major Threats and Challenges

The major threats and challenges that are influencing the health of the region’s biodiversity, include fragmentation and lack of connectivity of remnant vegetation, reduced extent and condition of flora and fauna communities, competition from invasive species, urban development and climate change.

Climate change

The potential impacts of higher temperatures on plants and animals include changes in the timing of life cycle events, as well as changes in distribution. For example, temperature sensitive plants and animals are generally expected to move to higher latitudes and altitudes in response to increasing temperatures. Plants and animals with highly specific habitat requirements, limited dispersal ability or those in fragmented habitats may find this difficult, leading to more local extinctions.

As the climate becomes less suitable for existing vegetation communities, it is likely that there will be a gradual change in species composition and dominance as some species and communities are replaced by others, leading to a shift in the floristics and structure of the community.

Pest plants and animals

Pest plants and animals are a major problem for biodiversity, as they compete with native species for resources, prey on native fauna, cause erosion and other physical disturbances, and can affect the functioning of ecosystems. Established terrestrial pest animals in the region include foxes, pigs, wild dogs, rabbits and hares. Overabundant native wildlife can also impact on the region’s biodiversity.

Deer are an increasing problem and are being observed in parts of the region where they have not been seen before. Deer are declared as ‘game’ rather than ‘pests’, and four deer species found in the region are legal to hunt. The impacts of deer on the environment include damage and destruction of native vegetation, increased revegetation costs, as well as damage to private land. They can also cause erosion and concentration of nutrients in sensitive environments2.

Land use change and under-representation

While large areas of high-quality native vegetation are conserved in the region’s parks and forests, a proportion is in cleared areas largely on private land. The losses from clearing on private land are thought to exceed the gains from revegetation and regeneration. Added to this is the challenge of under-representation whereby some bioregions and ecosystems are not sufficiently protected through the formal reserve system or permanent protection on private land.

The Gippsland Red Gum Grassy Woodland and Associated Native Grassland ecological community has been extensively cleared for agriculture, and is listed nationally as critically endangered. Similarly, coastal and wetland vegetation communities have also been extensively cleared, so the remnants of these communities are among the most important areas of native vegetation in the region.

While there is significant revegetation and remnant protection work occurring throughout the region, fragmentation remains a significant threat to the overall condition of biodiversity1.

The major drivers of change for the Biodiversity theme were identified through consultation with partner organisations as outlined below2.

Major drivers of change – Biodiversity

| CLIMATE CHANGE | POPULATION AND DEMOGRAPHIC TRENDS | LAND USE CHANGE | INDUSTRY OUTLOOK |

|---|---|---|---|

| ▪ Increase in both the frequency and intensity of bushfire ▪ Changes to water regimes affecting riparian, instream and wetland biodiversity ▪ Change in the range of weeds and emerging biosecurity risks in the region | ▪ Community awareness of biodiversity and valuing connection to nature ▪ Increased visitation to parks and reserves in the region | ▪ Urban and peri- urban growth and the intensification of agricultural land use is occurring in parts of the region ▪ Significant revegetation and remnant protection work is occurring throughout the region ▪ Fragmentation and under-representation remain significant threats to the overall condition of biodiversity ▪There are some parts of the region with large areas of land that is publicly owned and managed for conservation. There are also areas under Trust for Nature covenants and an increasing area under land management agreements | ▪ Greater recognition by industry to protect and enhance biodiversity outcomes, by avoiding minimising or offsetting impacts |

Opportunities and Management Directions

Priority management directions have been identified for the Biodiversity theme through a review of RCS3 and consultation with Traditional Owners, the community and partner organisations.

Established management directions will be delivered through existing sub-strategies and action plans.

Opportunities will be further developed or pursued through RCS implementation to help support Integrated Catchment Management in the region.

Priority opportunities and management directions for the Biodiversity theme

| MANAGEMENT DIRECTION | DETAILS | ESTABLISHED MANAGEMENT DIRECTION | OPPORTUNITY | PARTNERS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Undertake targeted action to protect high value habitat and reduce threats to biodiversity | Priorities informed by regional planning including weed/pest plant control, control of pest predators and herbivores, revegetation and permanent protection programs | ✔ | DELWP, WGCMA, Traditional Owners, Landcare, Local Government, Greening Australia, Gippsland Water, Parks Victoria, Private landholders, TfN | |

| Develop and implement Biolinks and habitat restoration programs | Initial priorities include the Bass Coast Biolink and Strzelecki-Alpine Biolink | ✔ | WGCMA, Landcare, Local Government, DELWP | |

| Support fire management programs that consider and incorporate Traditional Owner knowledge, ecological requirements and climate change | Including risk assessment, planning, planned burns and bushfire response | ✔ | DELWP, Parks Victoria, Traditional Owners | |

| Undertake targeted carbon sequestration revegetation programs | Aligned with priorities for biodiversity, waterways and land | ✔ | ✔ | WGCMA, DELWP, Greening Australia, Landcare, Local Government, Water Authorities |

| Implement Conservation Action Plans for the Gippsland Plains and Strzelecki Ranges and Wilsons Promontory Landscapes | Addressing priority threats to conservation assets in the Parks Victoria managed estate | ✔ | Parks Victoria, Traditional Owners, DELWP, WGCMA | |

| Implement the Greater Alpine Park Management Plan | Addressing priority threats to conservation assets in the Parks Victoria managed estate | ✔ | Parks Victoria, Traditional Owners, DELWP, WGCMA, | |

| Implement the Gunaikurnai Victorian Government Joint Management Plan | Addressing conservation and cultural assets in the Knob Reserve, Tarra Bulga NP, the Lakes NP & Gippsland Lakes CP | ✔ | GKTOLM, Parks Victoria, DELWP | |

| Implement the Victorian Alpine Peatlands Spatial Action Plan | Priorities include control of deer and transformative weeds and managing recreational access | ✔ | WGCMA, Parks Victoria, Traditional Owners, EGCMA, GBCMA, NECMA | |

| Deliver integrated catchment management initiatives in priority catchments | Perry River and Providence Ponds, Powlett River catchments | ✔ | WGCMA, Traditional Owners, Community representatives, Landcare, DELWP, DJPR, Local Government, Parks Victoria, TfN, Water Authorities | |

| Work with the community in priority areas to prepare whole of landscape integrated catchment management plans | Initial priorities include the Tarwin catchment and the Strzeleckis | ✔ | As above | |

| Address threats to biodiversity, waterways and Traditional Owner values on public land from illegal activities and inappropriate visitor behaviour | Potential actions include monitoring, compliance and communication and awareness raising | ✔ | Parks Victoria, DELWP, Local Government, Traditional Owners | |

| Develop approaches that address biosecurity risks and the impacts of emerging pest plants and animals | ✔ | DELWP, DJPR |

Regional Outcomes

This section sets out the long term (20-year) and medium term (6-year) outcomes for the region’s biodiversity. The regional outcomes include those aligned with the statewide outcomes framework as well as regionally specific outcomes developed in collaboration with RCS partners.

The overall RCS outcomes hierarchy can be found here with a more detailed matrix showing how the medium term outcomes align to local areas here.

Long term outcomes – by 2041 we will:

Regionally specific outcomes

- Increase the overall extent and connectivity of native vegetation

- Prevent additional species and communities from being listed as threatened under legislation.

Medium term outcomes – by 2027:

Aligned to the statewide outcomes framework

- An additional 5,000 ha of revegetation has been undertaken in priority locations to increase vegetation connectivity and enhance the condition of native vegetation*

- The area of sustained pest herbivore control has increased by 176,000 ha in priority locations*

- The area of sustained pest predator control has increased by 120,000 ha in priority locations*

- The area of sustained weed control has increased by 40,000 in priority locations*

- An additional 3,500 ha has been permanently protected*

Regionally specific outcomes

- Strategic biolinks have been identified and incorporated into planning schemes.

Footnotes

* These outcomes contribute to the regional targets and priority locations established through Biodiversity 2037 and TfN’s provisional targets for permanent protection on private land. Progress reporting against the outcomes will also account for RCS implementation in other priority locations informed by other regional planning processes.

Regional targets established through Biodiversity 2037 for the 2037 timeframe are as follows:

• Total area permanently protected since 2017 – 7000 ha

• Total area in priority locations under sustained weed control – 50,000 ha

• Total area of revegetation in priority locations for habitat connectivity since 2017 – 10,000 ha

• Total area in priority locations under sustained herbivore control – 220,000 ha

• Total area in priority locations under sustained pest predator control – 150,000 ha by 2037.

References

- DELWP. Protecting Victoria’s Environment – Biodiversity 2037, Summary. Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning . [Online] n.d. [Cited: 28 April 2021]

- RMCG. West Gippsland RCS Review and Renewal. Final Report. Torquay : RM Consulting Group for the West Gippsland Catchment Management Authority, 2020

- DELWP. Victorian Land Cover Time Series Data 1985 – 2019. [Spatial data] East Melbourne: : Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning. 2020

- DAWE. Collaborative Australian Protected Areas Database – Terrestrial and Marine. [Spatial data] Canberra: Australian Government Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment, 2021

- TfN. Trust for Nature Protected Areas (owned properties and TfN covenants). [Spatial data] East Melbourne, 2020

- VAGO. Protecting Victoria’s Biodiversity. October 2021. Independent assurance report to Parliament 2021-22. Victorian Auditor Generals Office, 2021.