Introduction

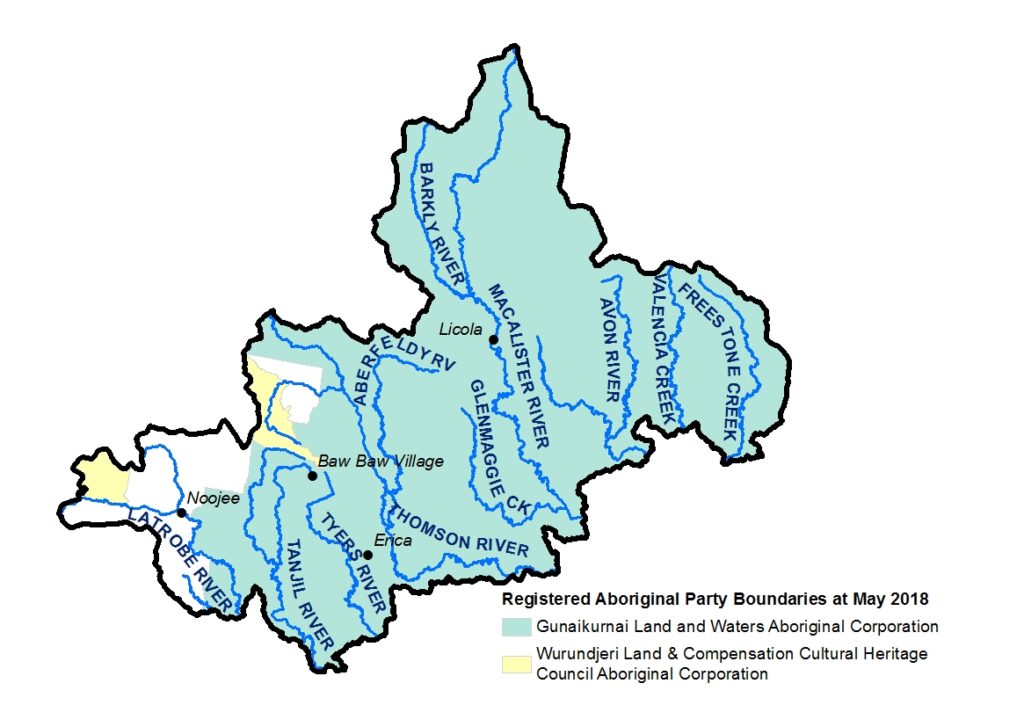

The Great Dividing Range and Foothills local area includes the Country of the Gunaikurnai and the Wurundjeri peoples. At present, there are also parts of the local area where formal recognition is not in place. Traditional Owners have a deep and continuing connection to the land and waters of the area and have an ongoing role in caring for Country.

The Gunaikurnai creation story began in the mountains: “The story of our creation starts with Borun, the pelican, who traversed our Country from the mountains in the north to the place called Tarra Warackel in the south. As Borun travelled down the mountains, he could hear a constant tapping sound, but he couldn’t identify the sound or where it was coming from. Tap tap tap. He traversed the cliffs and mountains and forged his way through the forests. Tap tap tap. He followed the river systems across our Country and created songlines and storylines as he went. Tap tap tap”12.

For the Wurundjeri community the natural world is also a cultural world; therefore, the Wurundjeri people have a special interest in preserving not just their cultural objects, but the natural landscapes of cultural importance. The acknowledgement of broader attributes of the landscape as cultural values that require protection (encompassing, among other things, a variety of landforms, ecological niches and habitats as well as continuing cultural practices and archaeological material) is essential to the identity and wellbeing of the Wurundjeri people13.

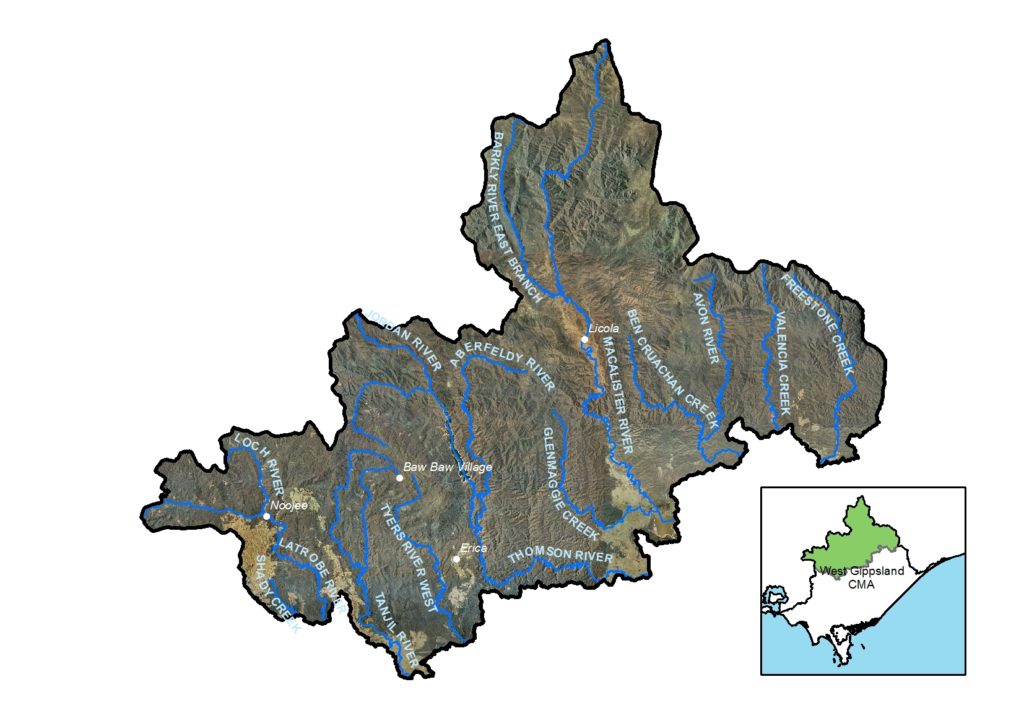

The Great Dividing Range and Foothills make up an important part of Victoria’s alpine and mountain environments. The local area includes the communities of Noojee, Erica, Licola, Walhalla and the Baw Baw Mountain village and are important gateways to the parks and reserves.

Approximately one quarter of the local area is permanently protected in public conservation reserves including the Baw Baw National Park, Moondarra State Park, Alpine National Park and the Avon Wilderness area. There are also large areas of public land reserved as State Forest.

The parks and reserves offer recreational, social and economic benefits to the whole of Victoria, whilst the foothills support agriculture and horticultural landuses as well as utilisation of forest resources for timber production and apiary1. Native forest and plantation forestry supports the timber, pulp and paper manufacturing sector. Timber harvesting is undergoing a major transition to plantation with the phase out of native forest timber harvesting by 20302.

The local area is home to a diverse range of flora and fauna. This includes several species found nowhere else, such as the Mountain Pygmy-Possum. The alpine peatlands are the focus of a multi-regional activity that extends across four Catchment Management Authority regions.

In broad terms, the vegetation communities and habitat in this area are in good condition, with over 94% of the local area covered by native vegetation6. Much of the area is isolated with limited access and disturbance; however, there are significant current and potential threats.

The historic sequence of fires, flood and drought has had a significant impact on the landscape to date and there are combined effects from weeds like willows and from deer that are well established in the mountains and foothills.

The soils form part of the eastern Victorian uplands land system. Granites and sedimentary rock dominate this area and many of the soils are coarse and medium textured. They support high ecological values and tourism associated with public land and the extensive scenic geography3;4.

Rivers that flow through the local area include the upper reaches of the Latrobe, Thomson, Macalister and Avon Rivers and their wild headwater tributaries. There are four major reservoirs within the local area: Blue Rock, Moondarra, Thomson and Lake Glenmaggie. The Thomson Reservoir is an extremely important source of water for Melbourne, making up about 60% of Melbourne’s total storage capacity.

Tourism and recreation are important economic activities in this local area with the natural assets attracting visitors for both summer and winter activities including four-wheel driving, camping, snow sports, walking and kayaking.

Landcare volunteers and groups in the local area are supported by the Latrobe Catchment Landcare Network and Maffra and District Landcare Network.

Collaborative action for Biodiversity

The local area incorporates the Upper Latrobe Foothills, Macalister Foothills, Baw Baw and Snowy Range landscapes of interest for Biodiversity Response Planning.

Baw Baw and the Snowy Range are focus areas due to the high biodiversity values and the potential to effectively address threats to flora and fauna.

Important vegetation communities include the Alpine Sphagnum Bogs and Associated Fens ecological community* (Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Federal), Cool Temperate Rainforest (Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act 1988 (Victorian)), Montane Riparian Thicket (Leadbeater’s possum habitat), and associated threatened flora and fauna.

The Baw Baw landscape supports one of the few large areas of forest in the eastern central highlands to have escaped the impact of large bushfires over the last 20 years (most of this area burnt in 1939), making this area a significant fire refuge for forest species11.

*Two components of the ecological community have been listed as threatened under the FFG Act 1988, these are the Alpine Bog Community and Fen (Bog Pool) Community.

Snapshot

This section provides an overview of the local area condition and trends for each of the themes, including information for a selection of indicators from the RCS Outcomes Framework.

Land

![]() Exposed soil ranged between 2.9% and 5.4% in the Baw Baw Shire Council area and 4.1% and 9.9% in Wellington Shire for the period 2000-20195 (NB: Local Government Areas extend beyond the local area boundary). The percentage of exposed soil in this local area and the region as a whole is much lower than other parts of Victoria and is associated with the moderate climate of the area.

Exposed soil ranged between 2.9% and 5.4% in the Baw Baw Shire Council area and 4.1% and 9.9% in Wellington Shire for the period 2000-20195 (NB: Local Government Areas extend beyond the local area boundary). The percentage of exposed soil in this local area and the region as a whole is much lower than other parts of Victoria and is associated with the moderate climate of the area.

![]() Landcover is dominated by native vegetation. Native trees and shrubs (525,079 ha) make up 93% of the local area. There is a smaller area (23,538 ha) of non-native pasture associated with grazing enterprises, hardwood and softwood plantations (3,111 ha). Between 1985 and 2019 the cover of native trees and shrubs remained stable whilst the non-native pasture declined slightly (-6%) 6.

Landcover is dominated by native vegetation. Native trees and shrubs (525,079 ha) make up 93% of the local area. There is a smaller area (23,538 ha) of non-native pasture associated with grazing enterprises, hardwood and softwood plantations (3,111 ha). Between 1985 and 2019 the cover of native trees and shrubs remained stable whilst the non-native pasture declined slightly (-6%) 6.

![]() Although representing only a very small proportion of the total area, there were increases in irrigated horticulture, exotic woody plants, forestry and urban land uses between 1985 and 20196.

Although representing only a very small proportion of the total area, there were increases in irrigated horticulture, exotic woody plants, forestry and urban land uses between 1985 and 20196.

![]() The combined production value of agriculture for the year 2015-16 was $49.9M. Milk production was the major commodity followed by cattle and calves. Hay, nurseries, cut flowers, eggs and poultry are other agricultural commodities in the local area.

The combined production value of agriculture for the year 2015-16 was $49.9M. Milk production was the major commodity followed by cattle and calves. Hay, nurseries, cut flowers, eggs and poultry are other agricultural commodities in the local area.

Biodiversity

![]() There was a loss of native scattered trees (-59%), native shrubs (-58%) and natural low cover vegetation (-7%) for the period 1985-20196. During the same period there was an increase in native grass herb (+39%) and native trees were relatively stable6.

There was a loss of native scattered trees (-59%), native shrubs (-58%) and natural low cover vegetation (-7%) for the period 1985-20196. During the same period there was an increase in native grass herb (+39%) and native trees were relatively stable6.

![]() Although only representing a small proportion of the total area, there was a decline in seasonal wetlands (-23%) and permanent wetlands (-47%)6.

Although only representing a small proportion of the total area, there was a decline in seasonal wetlands (-23%) and permanent wetlands (-47%)6.

![]() There is over 150,000 ha of habitat permanently protected through the reserve system (about 27% of the total area)7. 178 ha of habitat on private land was permanently protected through the establishment of Trust for Nature covenants between 2000-2019.

There is over 150,000 ha of habitat permanently protected through the reserve system (about 27% of the total area)7. 178 ha of habitat on private land was permanently protected through the establishment of Trust for Nature covenants between 2000-2019.

Water

The Water snapshot provides a summary from the Long Term Water Resource Assessment for Southern Victoria.

Waterways and wetlands

![]() Water availability has declined for the Thomson (-12%) and Latrobe (-5%) basins when compared with historical estimates1.

Water availability has declined for the Thomson (-12%) and Latrobe (-5%) basins when compared with historical estimates1.

![]() The volume of environmental water entitlements has been increased in the Thomson and Macalister River systems to support environmental water requirements and an entitlement has been created in the Latrobe River (and held within Blue Rock Reservoir).

The volume of environmental water entitlements has been increased in the Thomson and Macalister River systems to support environmental water requirements and an entitlement has been created in the Latrobe River (and held within Blue Rock Reservoir).

Despite changes to environmental entitlements, the proportion of water available for the environment has not increased because of declines in spills and unregulated inflows.

There has also been an increase in water available for consumptive use in the Latrobe system. This is due to the allocation of a previously unallocated share of flows into Blue Rock Reservoir. In the Thomson-Macalister these is evidence that environmental water is helping to restore the native fish population, including the threatened Australian grayling. However, overall, the findings for waterway health are inconclusive for both the Thomson and Latrobe basins.

During the period 2000-2019, the following was improved:

- 644 km of waterway

- 3,354 ha of riparian land

The area of perennial wetlands declined by 47% and seasonal wetlands by 23% between 1985 and 20196.

Community

The local area includes the towns of Noojee, Walhalla, Erica and Baw Baw Village in the west and Licola in the east. Surrounding these small towns and settlements are rural communities with a mix of agricultural producers and lifestyle properties. The mountain villages are popular tourist destinations in summer and winter.

Current and Future Challenges

![]() Key challenges in the Great Dividing Range and Foothills include:

Key challenges in the Great Dividing Range and Foothills include:

- Climate change

- Related extreme events including wildfire and floods.

The combined effects of climate change with existing threats from pest plants and animals and altered water regimes are a concern for agencies and the community.

The expansion of deer populations in this local area has been highlighted as a key challenge by agency partners and the community, with concerns about the impacts on waterways, vegetation, sensitive sub-alpine environments and agricultural land.

Pressure from increased recreational use and visitation impacts are also a challenge with potential impacts on vegetation, fauna and waterways.

Future changes to landuse such as an increase in plantation timber has also been highlighted as influencing water availability and increasing competition for land.

Overview of current and future management challenges for the Great Dividing Range and Foothills Local Area

| KEY MANAGEMENT CHALLENGES FOR LAND, WATER AND BIODIVERSITY | LAND | WATER | BIODIVERSITY | COMMUNITY CONCERNS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Altered water regime | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Erosion and soil degradation | ✔ | |||

| Pest plants | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Pest animals | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Land management practices (includes timber harvesting, land and livestock management practices) | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Recreational use and visitation impacts (includes facilities, activities and access) | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Inappropriate fire regimes | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Climate change and related extreme events (eg. wildfire, flood) | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

Opportunities and Priorities

The Traditional Owners of this local area, the Wurundjeri and Gunaikurnai peoples, have cared for this Country for thousands of years. Their place-based aspirations and priorities are outlined in the Wurundjeri Country Plan Country Plan (in preparation) and Gunaikurnai Whole of Country Plan.

There is a commitment from agencies and the community in this local area to continue to take a partnership approach to the management of land, water and biodiversity. New opportunities include planning for and taking action to address the combined effects of climate change and existing threats, cross-regional approaches for willow control and securing long-term funding for coordinated and targeted action.

The tables below set out the overarching Traditional Owner priorities that are relevant across all local areas and the other opportunities and priorities for agency partners and the community for this local area.

| TRADITIONAL OWNER PRIORITIES |

|---|

| ◾ Protecting cultural heritage from pressures associated recreation, land use changes and climate |

| ◾ Actively managing the water, fire, wildlife and biodiversity on Country in a culturally appropriate way |

| ◾ Having the authority to lead managing Country on behalf of the rest of the community |

| ◾ Seeking carbon production through forest restoration |

| ◾ Participating in economic opportunities, including employment and enterprise development associated with caring for Country |

| ◾ Access to water to restore customary practices, protect cultural values and uses and heal Country |

| ◾ Secure water rights to restore and reserve waterways and practice self-determination on how and where water is used for cultural, environmental or economic purposes. |

| OTHER LOCAL AREA OPPORTUNITIES AND PRIORITIES |

|---|

| ◾ Protect and improve biodiversity including through permanent protection and targeted actions to reduce threats |

| ◾ Continue to implement the Alpine Peatlands Spatial Action Plan and Greater Alpine National Park Management Plan |

| ◾ Implement the Strzelecki-Alpine Biolink, including establishing provisions in local planning schemes |

| ◾ Improve visitor infrastructure and address illegal and un-authorised activities on public land (e.g. dumping, firewood removal, off-road driving) |

| ◾ Undertake integrated control programs to address pest plants and animals (including the increasing impact of deer) |

| ◾ Explore the improved use of fire including traditional burning practices to support ecological communities |

| ◾ Work together to understand and implement climate change adaptation priorities at the local scale |

| ◾ Increase community awareness of the environment and providing opportunities for community participation |

| ◾ Support farmers and forestry operators to implement practices that improve land management and reduce off-site impacts |

| ◾ Support Traditional Owners’ aspirations for and participation in land, water and biodiversity management |

| ◾ Complete works to protect and rehabilitate waterways and ensure the efficient and effective use of environmental water (e.g. Tyers River fish passage) |

| ◾ Investigate and implement options to address water recovery targets (for Traditional Owner, environmental and recreational values). |

Community perspectives

What does the Great Dividing Range and Foothills look like in the future?

“The challenges can be summed up with ferals, fire and people.”

“A strong focus on keeping the natural habitat for our flora and fauna. The eradication and exclusion of feral animals in our forests and water environments. The proper care and management of public access areas which have become degraded by human activities.”

“Mitigation and adaptation to the impacts of climate change – waterways, landscape and communities.”

The top land, water and biodiversity management actions identified by community members were:

- Control pest animals (eg. deer)

- Control pest plants (eg. willow, blackberries)

- Manage the impacts of increased recreation and tourism on natural areas

- Fencing of waterways and native vegetation

- Community engagement and participation

- Managing fire risk

- Initiatives to support climate change adaptation.

The top areas of focus for climate change adaptation were:

- Maintain a diversity of habitats, environments and species to maximise the chance of survival

- Support the transition of ecosystems that are most vulnerable to a changing climate

- Support shared learning between communities and agencies to help drive adaptation

- Increase carbon sequestration through activities such as revegetation and soil improvement.

The top areas for helping communities and industries to participate in land, water and biodiversity management were:

- Collaboration between agencies and community/industry on projects at a local level

- Opportunities to contribute knowledge to planning and decision making

- Opportunities to participate in citizen science and in-ground activities

- Grants or incentives to undertake projects.

Management Directions and Regional Outcomes

Management directions are the overarching strategies to guide agency and community collaboration. The agency and community priorities outlined above will help to realise the management directions at the local area scale.

Implementation will be guided by regular local area partnership forums and implementation planning processes that prioritise effort with consideration to value for money and issues of feasibility and risk.

Priority management directions have been defined for each theme: Land, Water, Biodiversity, Coast and Marine and Community, Traditional Owners and Climate Change.

The RCS outcomes hierarchy can be found here with a more detailed matrix showing how the medium term outcomes align to local areas here.

Further details on RCS implementation can be found here.

References

- WGCMA. West Gippsland Regional NRM Climate Change Strategy. West Gippsland CMA, Traralgon, Victoria, 2016

- RMCG. West Gippsland Regional Catchment Strategy Review and Renewal Report. Prepared by RMCG for the West Gippsland Catchment Management Authority, 2020

- WGCMA. West Gippsland Soil Erosion Management Plan. West Gippsland Catchment Management Authority, 2008

- WGCMA. West Gippsland Regional Catchment Strategy 2013- 2019. Traralgon: West Gippsland Catchment Management Authority, 2013

- Van Dijk, A and Summers, David. Australia’s Environment Explorer, The Australian National University. Exposed Soil. [Online] 27 November 2020

- DELWP. Victorian Land Cover Time Series Data 1985 – 2019 . East Melbourne : Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning , 2020a

- DAWE. Collaborative Australian Protected Areas Database (CAPAD) – Terrestrial & Marine. [Spatial Layer] Canberra : Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment, 2021

- DELWP. Long Term Water Resource Assessment for Southern Victoria. Basin by Basin Results. East Melbourne : Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning, 2020

- ABS. Agricultural Census: Agricultural Data – 2005-06, 2010-11 and 2015-16. Canberra : Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2020

- DELWP. Draft Gippsland Regional Adaptation Strategy. Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning, n.d

- DELWP. Biodiversity Response Planning Fact Sheets. Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning. [Online] 2021

- GLAWAC. Gunaikurnai Whole of Country Plan. Gunaikurnai Land and Waters Aboriginal Corporation. 2015

- WWW. Wurundjeri – Our Story – Significant Places. Wurundjeri Woi-Wurrung Aboriginal Cultural Heritage Corporation. [Online]. n.d.