Introduction

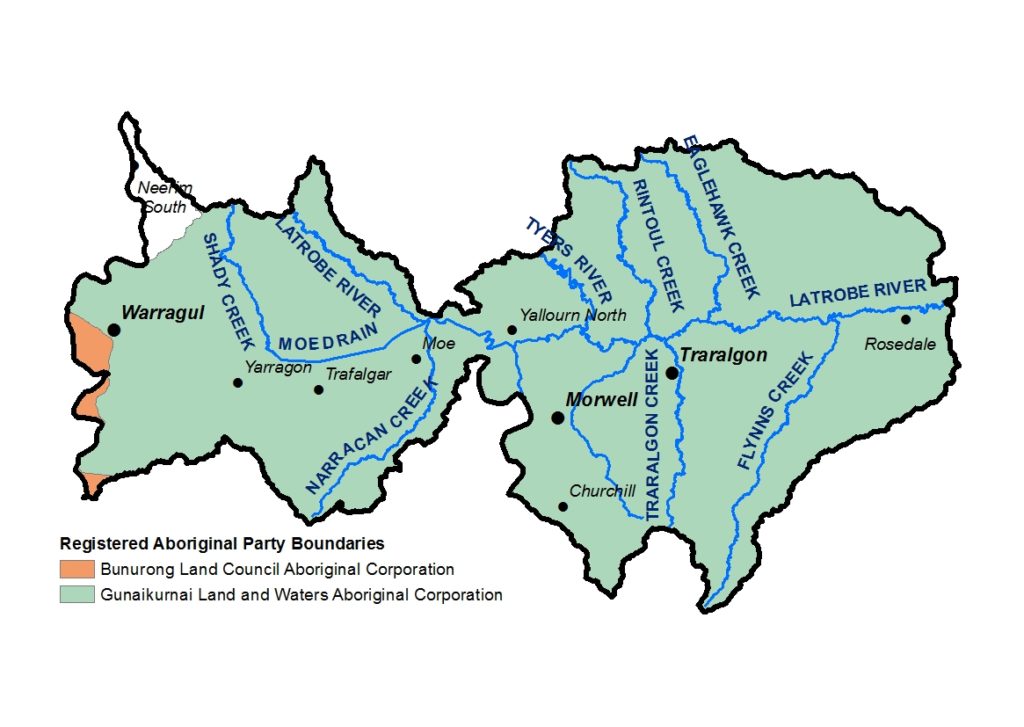

The Latrobe local area includes the Country of the Gunaikurnai Traditional Owners and Bunurong Traditional Owners. At present, there are also parts of the local area where formal recognition is not in place. Traditional Owners have a deep and continuing connection to the area and have an ongoing role in caring for Country.

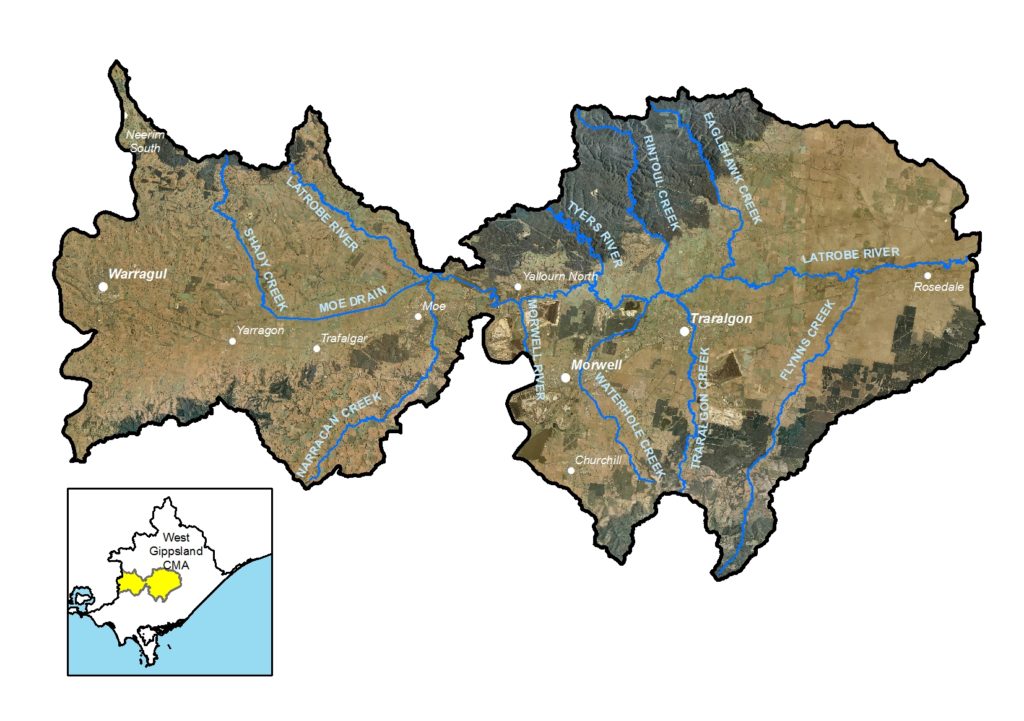

The Latrobe local area extends from Warragul in the west to Rosedale in the east and falling between the Great Dividing Range and Strzelecki Ranges. Rainfall varies across the local area with high and generally reliable rainfall in the west compared with the eastern end.

The local area includes the major population centres of Warragul, Moe, Morwell and Traralgon and the smaller townships of Yarragon, Trafalgar, and Rosedale. The Latrobe local area supports several major industries and related strategic assets including major water supply dams, significant brown coal deposits and major power stations in the Latrobe Valley1.

With its proximity to Melbourne and access to natural resources, the Latrobe local area has many advantages; however, the communities that live and work in the Latrobe Valley are faced with significant challenges.

Economic restructuring and declining employment associated with the closure of the Hazelwood mine and power plant, and the future closures of Yallourn and Loy Yang are major challenges for the community in this local area. The plans for mine rehabilitation and future development also have the potential to impact water sharing and environmental values. These factors have made the Latrobe Valley the focus for a significant program for economic transition with the community calling for a ‘cleaner and greener’ future1;2.

Within the local area, there is a network of community groups and volunteers with a strong interest in the natural environment. Landcare volunteers and groups in the local area are supported by the Latrobe Catchment Landcare Network and Maffra and Districts Landcare Network.

The Latrobe River is the major river system in the local area flowing from the Great Dividing Range in the west and discharging to Lake Wellington, part of the Gippsland Lakes Ramsar Site. Urban waterways include parts of Traralgon Creek, Waterhole Creek and Hazel Creek. Other tributaries to the Latrobe River include Shady Creek, Tyers River, Moe River, Morwell River, Rintoul and Eaglehawk Creeks3.

Water is a valuable resource in the local area with Lake Narracan together with Blue Rock and Moondarra Reservoirs in the adjacent local area providing water that supports industry, urban, agriculture and domestic consumptive uses as well as the environment. There are multiple entitlements and provisions for environmental water in the Latrobe Basin including passing flows and limits on allocations for consumptive users4.

The Latrobe local area includes soils of the riverine plain and are made up of sediments eroded from the surrounding ranges and are variable. Soil and land are highly valued for supporting agricultural production. The soil and land asset supports several threatened ecological vegetation classes. Soils in the west tend to be finer textured and more acid, whilst in the east, there is a tendency for soils to be more sodic with more sand in the surface layers5;6.

The western part of the local area includes key areas of fragmented habitat within a corridor (biolink) that supports 1,296 species of flora and 339 species of fauna, including the genetically diverse South Gippsland koala population. Areas of Damp Forest and Lowland Forest within this corridor are a focus for creating a link across the Latrobe City Council area with core habitat areas in the Strzelecki Ranges and Great Dividing Range7.

Collaborative action for Biodiversity

The local area incorporates parts of six landscapes of interest for the Biodiversity Response Planning process.

The eastern part of the local area includes part of the Mullungdung Darriman and Red Gum Plains focus areas for Biodiversity Response Planning. Important vegetation communities include the Gippsland Red Gum Grassy Woodland and associated Native Grassland ecological community, Seasonal Herbaceous Wetlands of the Temperate Lowland Plains (Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Federal)) and Forest Red Gum Grassy Woodland Community (Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act 1988 (Victorian)) as well as numerous threatened flora and fauna species8.

Snapshot

This section provides an overview of the local area condition and trends for the RCS asset themes. The indicators form part of the state-wide outcomes framework required by the guidelines for the preparation of Regional Catchment Strategies.

Land

![]() Exposed soil ranged between 2.0% and 5.4% in the Baw Baw Shire Council, 6.4% and 10.3% in Latrobe City and 4.1% and 9.9% in Wellington for the period 2000-20199.

Exposed soil ranged between 2.0% and 5.4% in the Baw Baw Shire Council, 6.4% and 10.3% in Latrobe City and 4.1% and 9.9% in Wellington for the period 2000-20199.

![]() Non-native pasture (associated with grazing enterprises) is the dominant landcover (120,984 ha), followed by native trees and shrubs (40,015 ha), forestry (19,255 ha), urban (7,823 ha) and irrigated horticulture (6,363 ha) 10 .

Non-native pasture (associated with grazing enterprises) is the dominant landcover (120,984 ha), followed by native trees and shrubs (40,015 ha), forestry (19,255 ha), urban (7,823 ha) and irrigated horticulture (6,363 ha) 10 .

![]() The area of land used for dryland cropping, irrigated horticulture, urban, exotic woody plants and forestry increased between 1985 and 2019. The area of non-native pasture and native grassland declined over the same period 10 .

The area of land used for dryland cropping, irrigated horticulture, urban, exotic woody plants and forestry increased between 1985 and 2019. The area of non-native pasture and native grassland declined over the same period 10 .

![]() The combined production value of agriculture for the year 2015-16 was $276.6M. Milk production was the major commodity, followed by cattle and calves and vegetables12.

The combined production value of agriculture for the year 2015-16 was $276.6M. Milk production was the major commodity, followed by cattle and calves and vegetables12.

Biodiversity

![]() There was an increase in natural low cover vegetation (+31%) for the period 1985-201910.

There was an increase in natural low cover vegetation (+31%) for the period 1985-201910.

![]() There was a loss in the following over the same period:

There was a loss in the following over the same period:

- -52% native shrubs

- -30% native scattered trees

- -12% native grass herb.

The cover of native trees remained relatively stable10.

![]() 3,658 ha of terrestrial habitat is permanently protected through the reserve system (about 2% of the total area) for the Latrobe local area11.

3,658 ha of terrestrial habitat is permanently protected through the reserve system (about 2% of the total area) for the Latrobe local area11.

580 ha of habitat on private land was protected through the establishment of Trust for Nature covenants between 2000-2019.

Water

The Water snapshot provides a summary from the Long Term Water Resource Assessment for Southern Victoria.

There is currently 829.8GL of surface water available in the Latrobe River system. 78% of surface water is available for the environment1.

The Blue Rock Environmental Entitlement provides rights to just under a 10 per cent share of inflow and storage capacity in Blue Rock Reservoir to provide targeted environmental water deliveries in the Latrobe system.

![]() Water availability in the Latrobe basin has declined by 5% when compared with historical estimates.

Water availability in the Latrobe basin has declined by 5% when compared with historical estimates.

Changes in water-sharing arrangements, climate and landuse change are understood to have contributed to a decline in surface water flows in the Latrobe Basin. Interception of water by dams may have contributed to a decline. Licensed groundwater pumping reduced waterway flow across the basin by 0.1 GL/year in the Moe Groundwater Management Area (GMA), which is less than 1% of annual average flows and low flows.

There have been moderate declines in aspects of the flow regime since the Sustainable Water Strategy (2011). There were improvements in winter baseflows in reaches with flows delivered under the environmental entitlement; however less than half the recommended winter and summer freshes were achieved.

These declines in aspects of the flow regime coincided with mixed trends in waterway health indicators. Overall, the findings for waterway health for reasons related to flow are inconclusive.

Dry conditions during 2018/19, low river flows, and ash from 2019 bushfire events in the catchment all present risks to the waterway health in the Latrobe Basin4.

![]() Groundwater resources include the Moe and Denison Groundwater Management Areas.

Groundwater resources include the Moe and Denison Groundwater Management Areas.

Monitoring of the Groundwater Management Areas shows there has been a long-term decline of less than 1m in the upper aquifer of the Denison GMA and a decline of ≻2m for the deep confined aquifer of the Moe GMA.

Shallow groundwater levels are also modified around the Latrobe Valley coal mines where local declines in water levels are likely to have occurred.

Groundwater levels have declined in the deep aquifers associated with groundwater depressurisation of the Latrobe Valley coal mines. Groundwater in the deep aquifers is not connected to waterways and therefore, these declines are unlikely to have contributed to declining flows in rivers and streams4.

Waterways and wetlands

Between 2000 and 2019 the following activities were undertaken:

- 195 km of riparian improvement

- 2,400 ha of riparian improvement.

This included:

- 906 ha weed control

- 520 ha revegetation activities.

![]() The area of perennial wetlands declined by 64% and seasonal wetlands declined by 38% between 1985 and 201910.

The area of perennial wetlands declined by 64% and seasonal wetlands declined by 38% between 1985 and 201910.

Community

The local area includes several major centres that are on a growth trajectory including Trafalgar, Rosedale and Traralgon.

The Drouin-Warragul corridor is a key growth area for Baw Baw Shire and the peri-urban area around Melbourne. The population of these areas are expected to increase by up to 66% between 2016-361.

Current and Future Challenges

![]() The Latrobe local area is undergoing a major transformation as a result of economic transition and long-term plans to rehabilitate the Latrobe Valley’s coal mines. These changes will result in both challenges and opportunities for land, water, and biodiversity management.

The Latrobe local area is undergoing a major transformation as a result of economic transition and long-term plans to rehabilitate the Latrobe Valley’s coal mines. These changes will result in both challenges and opportunities for land, water, and biodiversity management.

Population pressures associated with increased urban and peri-urban development are a current challenge with concerns about the potential impacts on biodiversity, waterways, and competition for agricultural land.

There are areas with high flood risk in the local area and managing the risks of flooding in light of climate change and development pressures are an ongoing challenge.

Habitat fragmentation and the impacts of pest plants and animals have also been identified by community members and agency partners as key challenges in the local area.

Raising the profile of the natural values of the local area and greater action by agencies to protect and manage land, water and biodiversity were other issues identified during community consultation for the RCS.

Overview of current and future management challenges for the Latrobe Local Area

| KEY MANAGEMENT CHALLENGES FOR LAND, WATER AND BIODIVERSITY | LAND | WATER | BIODIVERSITY | COMMUNITY CONCERNS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pest plants | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Habitat fragmentation | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Population growth and urban expansion | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Reduced water availability | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Altered flow regime | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Pest animals | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Uncontrolled runoff/poor water quality | ✔ | |||

| Soil degradation | ✔ | |||

| Climate change and related extreme events (e.g. wildfire, flood, drought). | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

Opportunities and Priorities

Traditional Owner priorities

The Traditional Owners of this local area, the Bunurong and Gunaikurnai peoples, have cared for this Country for thousands of years. Their place-based aspirations and priorities are outlined in the Bunurong Country Plan (in preparation) and Gunaikurnai Whole of Country Plan.

Community members and agency partners have highlighted the opportunity to support a ‘clean green’ Latrobe as part of the transformation of the local economy. There are clear links with this aspiration and the priorities for land, water, and biodiversity management.

The West Gippsland Floodplain Management Strategy analysed flood risk across the region and identified the priority actions to minimise this risk. The actions in the Strategy are regularly reviewed by the partner agencies to ensure the actions remain relevant and continue to focus on the highest priority risks to our communities.

The tables below set out the overarching Traditional Owner priorities that are relevant across all local areas and the other opportunities and priorities for agency partners and the community for this local area.

| TRADITIONAL OWNER PRIORITIES |

|---|

| ◾ Protecting cultural heritage from pressures associated recreation, land use changes and climate change |

| ◾ Actively managing the water, fire, wildlife and biodiversity on Country in a culturally appropriate way |

| ◾ Having the authority to lead managing Country on behalf of the rest of the community |

| ◾ Seeking carbon production through forest restoration |

| ◾ Participation in economic opportunities, including employment and enterprise development associated with caring for Country |

| ◾ Access to water to restore customary practices, protect cultural values and uses and heal Country |

| ◾ Secure water rights to restore and reserve waterways and practice self-determination on how and where water is used for cultural, environmental or economic purposes. |

| OTHER LOCAL AREA OPPORTUNITIES AND PRIORITIES |

|---|

| ◾ Prevent further loss of biodiversity through permanent protection and targeted actions to reduce threats |

| ◾ Implement the Strzelecki-Alpine Biolink, including establishing provisions in local planning schemes |

| ◾ Improve recreational facilities and manage human access in areas of high biodiversity value |

| ◾ Increase community awareness of the environment and provide opportunities for community participation |

| ◾ Investigate and implement planning scheme measures to manage potential impacts from development / population growth on agricultural land, wetlands, water quality and biodiversity |

| ◾ Support farmers and forestry operator to implement practices that improve land management, reduce off-site impacts and increase water use efficiency |

| ◾ Support Traditional Owners’ aspirations for and participation in land, water and biodiversity management |

| ◾Address the current and future risk of flooding including through integrated water management options |

| ◾ Complete works to improve the amenity of waterways in urban areas. (Traralgon Creek, Waterhole Creek) |

| ◾ Investigate and implement options to address water recovery targets (for Traditional Owner, environmental and recreational values) |

| ◾ Complete works to protect and rehabilitate waterways and riparian areas. |

Community perspectives

What does the Latrobe local area look like in the future?

“Well vegetated farms with corridors linking islands of native vegetation in the landscape.”

“Increased native vegetation in conjunction with productive agriculture.”

“We have become more sustainable in all aspects of water use.”

“Riparian zones are revegetated and protected.”

“Rehabilitated coal mines.”

The top land, water and biodiversity management actions identified by community members were:

- Retain and restore native vegetation

- Fencing waterways and native vegetation

- Community engagement and participation

- Support agricultural practices that improve soil health, productivity and water use efficiency

- Improve our knowledge of land, water and biodiversity and the effectiveness of our actions

- Planning and development controls to address the impacts of landuse change.

The top areas of focus for climate change adaptation were:

- Maintain a diversity of habitats, environments and species to maximise the chance of survival

- Increase carbon sequestration through activities such as revegetation and soil improvement

- Conduct monitoring and research that improves our ability to plan for and adapt to climate change.

The top areas for helping communities and industries to participate in land, water and biodiversity management were:

- Grants or incentives to undertake projects

- Collaboration between agencies and community/industry on projects at a local level

- Information/advice to improve knowledge

- Funding for research and development.

Management Directions and Regional Outcomes

Management directions are the overarching strategies to guide agency and community collaboration. The agency and community priorities outlined above will help to realise the management directions at the local area scale.

Implementation will be guided by regular Local Area partnership forums and implementation planning processes that prioritise effort with consideration to value for money, and issues of feasibility and risk.

Priority management directions have been defined of each theme: Land, Water, Biodiversity, Traditional Owners, Community and Climate Change.

The RCS outcomes hierarchy can be found here with a more detailed matrix showing how the medium term outcomes align to local areas here.

Further details on RCS implementation can be found here.

References

- RMCG. West Gippsland Regional Catchment Strategy Review and Renewal Report. Prepared by RMCG for the West Gippsland Catchment Management Authority, 2020

- LCC. Latrobe Rural Land Use Strategy. Latrobe City Council , 2019

- WGCMA. West Gippsland Waterway Strategy 2014-22. Traralgon : West Gippsland Catchment Management Authority, 2014

- DELWP. Long Term Water Resource Assessment for Southern Victoria. Basin by Basin Results. East Melbourne: Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning, 2020

- WGCMA. West Gippsland Soil Erosion Management Plan. West Gippsland Catchment Management Authority, 2008

- WGCMA. West Gippsland Regional Catchment Strategy 2013- 2019. Traralgon: West Gippsland Catchment Management Authority, 2013

- LCC. Strzelecki-Alpine Biolink. Gorman, M & Fraser, C for the Latrobe City Council, 2018

- DELWP. Biodiversity Response Planning Fact Sheets. Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning. [Online] 2021

- Van Dijk, A and Summers, David. Australia’s Environment Explorer, The Australian National University. Exposed Soil. [Online] 27 November 2020

- DELWP. Victorian Land Cover Time Series Data 1985 – 2019. East Melbourne: Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning , 2020a

- DAWE. Collaborative Australian Protected Areas Database (CAPAD) – Terrestrial & Marine. [Spatial Layer] Canberra: Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment, 2021

- ABS. Agricultural Census: Agricultural Data – 2005-06, 2010-11 and 2015-16. Canberra: Australian Bureaus of Statistics, 2020

- BLCAC. Bunurong Land Council Aboriginal Corporation Appointed Registered Aboriginal Parties Area. Frankston : Bunurong Land Council Aboriginal Corporation , Undated

- CES. Victoria: State of the Environment 2013. Melbourne : Commissioner for Environmental Sustainability Victoria, 2013

- DELWP. LVRRS Essentials. Latrobe Valley Regional Rehabilitation Strategy (LVRRS). [Online] 16 11 2020

- DELWP. Draft Gippsland Regional Adaptation Strategy. Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning, n.d

- id. Wellington Shire Council Locality Snapshots. [Online] January 2021.