Introduction

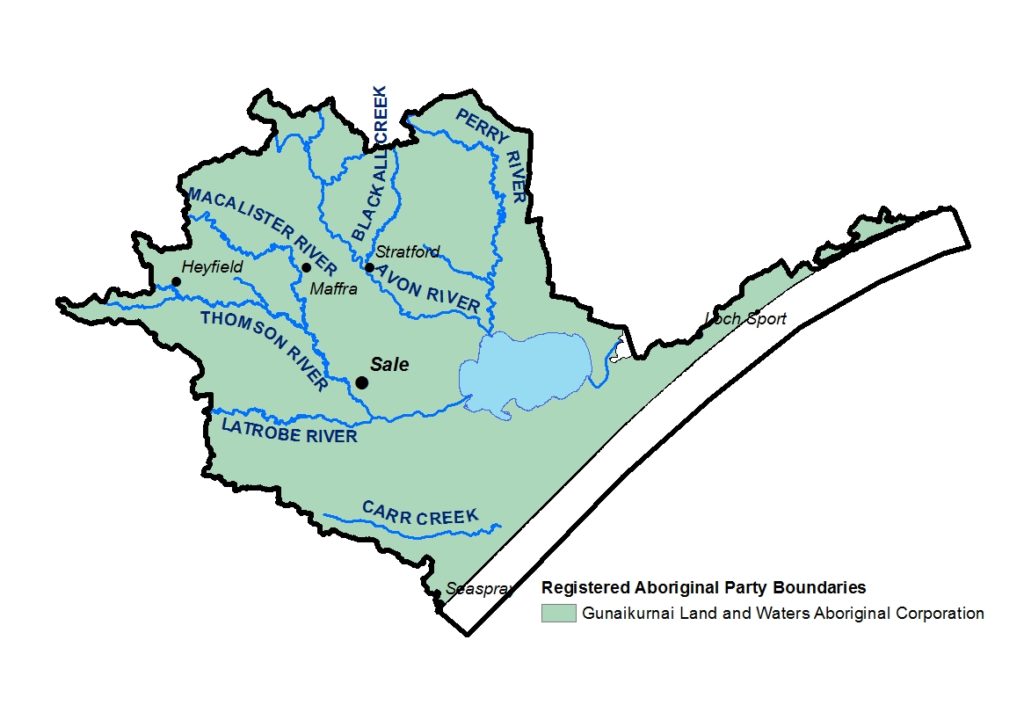

The Gunaikurnai are the Traditional Owners of the Gippsland Lakes and Hinterland local area.

The land around the Gippsland Lakes has been occupied by the Gunaikurnai peoples for thousands of years. The Gunaikurnai have a deep, longstanding connection with the area and have an ongoing role in caring for Country. Fishing, camping, hunting and gathering remain key traditional practices across the landscape, and the area holds significant physical and intangible cultural heritage values across many sites17.

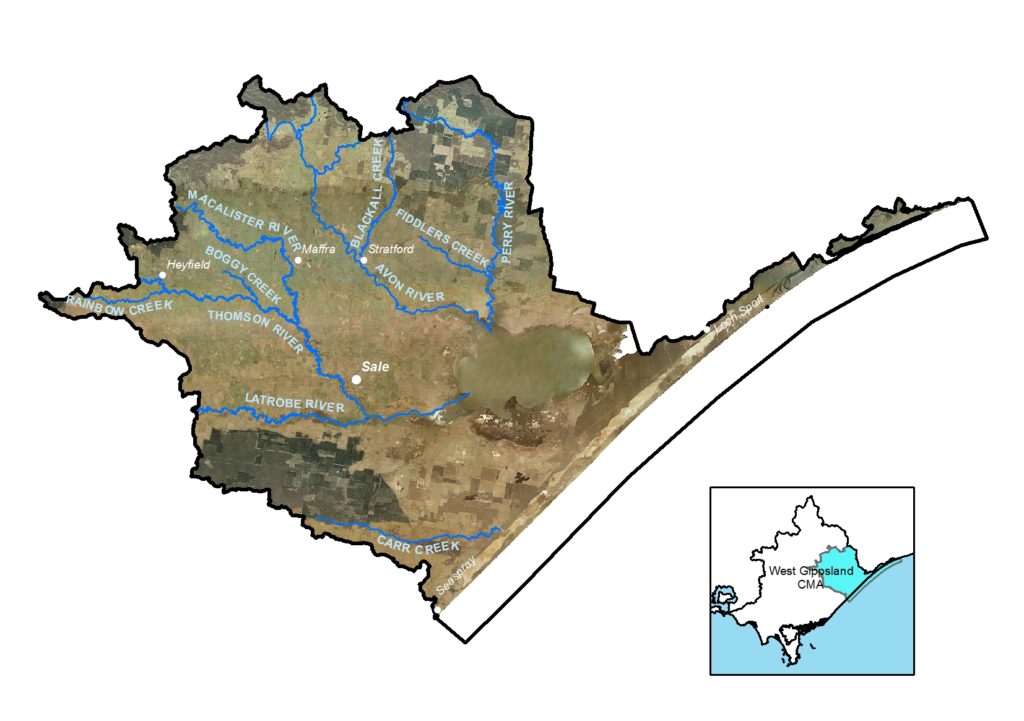

The Gippsland Lakes and Hinterland local area is characterised by the iconic Gippsland Lakes Ramsar site and incorporates part of the Red Gum Plains extending to the 90-Mile beach at the coast. The major rivers (Latrobe, Thomson, Macalister, Avon, and Perry) have extensive floodplains with freshwater and brackish wetland environments that link with Lake Wellington.

Towns in the local area include Heyfield, Sale, Maffra and Stratford to the north and Seaspray and Loch Sport on the coast. The broader Gippsland Lakes and coast are highly valued for tourism and recreational activities and are also critical to the regional economy and are an important source of employment.

The local area is within a largely fragmented agricultural landscape that incorporates the Macalister Irrigation District (MID), the major irrigation hub in the region. Dryland and irrigated agriculture including dairy, horticulture and other forms of livestock production and cropping support the local economy and community. Irrigation in the MID (alone) supports over $650 million in overall economic activity annually1.

Changes in land use have been observed in the local area with a shift from dairy to horticulture within the MID and a trend towards larger-scale operations across irrigated and non-irrigated agriculture2.

Landcare volunteers and groups in the local area are supported by the Latrobe Catchment Landcare Network and Maffra and District Landcare Network. There is a history of collaboration between agencies, landholders, community groups and industry in this local area and across the West and East Gippsland CMA regions. Efforts have been focussed on improving the health of the Lakes, sustainable irrigation, protecting and restoring native vegetation, waterways, and wetlands in the hinterland area.

Surface water is a valuable resource in the local area supporting agriculture, domestic and urban supply, and the environment. There are multiple provisions for environmental water including two environmental entitlements in the Thomson-Macalister system and two in the Latrobe system. The Avon system is unregulated and environmental provisions are provided entirely through above cap flows5. Plans for mine rehabilitation and future development in the Latrobe local area also have the potential to impact water sharing and environmental values associated with the Gippsland Lakes.

Increased temperatures, decreased rainfall and rising sea levels are having a profound effect on the Gippsland Lakes. Increasing salinity, increased inundation of intertidal communities and potential salinisation of freshwater wetlands are all serious risks to the values of the Gippsland Lakes. There is also predictions of increased fire and flood events, which could lead to more frequent inflows of nutrients and sediments to the system, further impacting aquatic communities.

Groundwater resources include the Moe, Denison, Rosedale, and Sale Groundwater Management Areas. The shallow aquifers have high connectivity to surface water systems including the Avon, Thomson and Macalister Rivers and are an important resource for domestic, livestock irrigation and urban water supply4. Groundwater has historically been associated with salinity impacts in and around the MID. Since their peak in the 1990s, water tables have fallen across the MID. This reflects the influence of the Millennium drought and major improvements in irrigation efficiency1.

The local area includes soils of the riverine and coastal plains. The soils of the riverine plain are made up of sediments eroded from the surrounding ranges and are variable5. The coastal plain is characterised by dunefield landscapes along the shoreline, dominated by wind-blown sands with drainage extremes5. Soil and land are highly valued for supporting agricultural production. The soil and land asset supports threatened ecological vegetation classes4.

Collaborative action for Biodiversity

The local area incorporates parts of three landscapes of interest for Biodiversity Response Planning process; Mullungdung Darriman, Red Gum Plans and Gippsland Lakes.

Important vegetation communities include the Gippsland Red Gum Grassy Woodland and associated Native Grassland ecological community, Seasonal Herbaceous Wetlands of the Temperate Lowland Plains, Subtropical and Temperate Coastal Saltmarsh (Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Federal)) as well as Plains Grassland (South Gippsland) and Forest Red Gum Grassy Woodland Community (Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act 1988 (Victorian)). The area also incorporates the unique Perry River Sandy Flood Scrub Ecological Vegetation Class (EVC) and Billabong Flora and Fauna Reserve, a Directory of Important Wetland. Along the coast, the barrier dune system separates the Gippsland Lakes from Bass Strait. In this area Coastal Banksia Woodlands, Heathy Woodlands and Saltmarsh are the dominant native vegetation communities4;14.

Snapshot

This section provides an overview of the local area condition and trends for RCS asset themes, including information for a selection of indicators from the state-wide outcomes framework.

Land

![]() Exposed soil ranged between 4.1% and 9.9% in Wellington Shire over the period 2000-20197. Exposed soil on agricultural land can be an issue in this part of the region during extended dry periods.

Exposed soil ranged between 4.1% and 9.9% in Wellington Shire over the period 2000-20197. Exposed soil on agricultural land can be an issue in this part of the region during extended dry periods.

![]() Non-native pasture (associated with livestock enterprises) (91,475 ha) and native trees and shrubs (90,998 ha) are the dominant landcover types in the Gippsland Lakes and Hinterland. Irrigated horticulture (48,361 ha) and forestry (22,408 ha) are also major landuses8.

Non-native pasture (associated with livestock enterprises) (91,475 ha) and native trees and shrubs (90,998 ha) are the dominant landcover types in the Gippsland Lakes and Hinterland. Irrigated horticulture (48,361 ha) and forestry (22,408 ha) are also major landuses8.

![]() Irrigated horticulture, urban and forestry dryland cropping, exotic woody plants, forestry and urban land uses increased between 1985 and 20198.

Irrigated horticulture, urban and forestry dryland cropping, exotic woody plants, forestry and urban land uses increased between 1985 and 20198.

![]() The combined production value of agriculture for 2015-16 was $276.6M. Milk production was the major commodity, followed by cattle and calves and vegetables12.

The combined production value of agriculture for 2015-16 was $276.6M. Milk production was the major commodity, followed by cattle and calves and vegetables12.

Biodiversity

![]() There was an increase in native grass herb (+41%) and natural low cover (+19%) for the period 1985-2019. The area of native scatter trees declined (-52%) over the same period. The area of native shrubs remained relatively stable and native trees increased (+5%)8.

There was an increase in native grass herb (+41%) and natural low cover (+19%) for the period 1985-2019. The area of native scatter trees declined (-52%) over the same period. The area of native shrubs remained relatively stable and native trees increased (+5%)8.

![]() 42,314.9 ha of terrestrial habitat is permanently protected through the reserve system (about 12% of the total area)9.

42,314.9 ha of terrestrial habitat is permanently protected through the reserve system (about 12% of the total area)9.

Water

The Water snapshot provides a summary from the Long Term Water Resource Assessment for Southern Victoria.

Surface Water

There is 829.8 GL of surface water available in the Latrobe Basin and 914.1 GL in the Thomson Basin (incorporating the Thomson, Macalister and Avon Rivers).

78% of surface water in the Latrobe Basin is available to the environment, and in the Thomson Basin, 58% is available to the environment3.

There have been increases to both the Thomson River environmental entitlement, and the Macalister River environmental entitlement. However, overall water availability in both the Thomson and Latrobe Basins have declined when compared with historical estimates.

![]() In the Thomson-Macalister system declines in water availability have been linked to changes in water-sharing arrangements, climate, and groundwater extraction

In the Thomson-Macalister system declines in water availability have been linked to changes in water-sharing arrangements, climate, and groundwater extraction

![]() In the Latrobe system, climate, and large scale landuse change to more intensive water activities are also understood to have contributed to declines in water availability. Interception by stock and domestic dams (in the mid and upper catchment) may also be a contributing factor.

In the Latrobe system, climate, and large scale landuse change to more intensive water activities are also understood to have contributed to declines in water availability. Interception by stock and domestic dams (in the mid and upper catchment) may also be a contributing factor.

![]() In the Thomson Basin there have been, on average, moderate improvements in several aspects of the flow regime since the additions to the Thomson and Macalister environmental entitlements.

In the Thomson Basin there have been, on average, moderate improvements in several aspects of the flow regime since the additions to the Thomson and Macalister environmental entitlements.

This includes the provision of baseflows, and winter freshes which facilitate sand scour of channels, improve vegetation condition and provide opportunities for fish movement.

![]() There has been a decline, particularly in the Macalister River, of summer freshes, which provide important breeding cues for several species of native fish3.

There has been a decline, particularly in the Macalister River, of summer freshes, which provide important breeding cues for several species of native fish3.

![]() In the Latrobe River system there were improvements to winter baseflows in reaches with flows delivered under the environmental entitlement; however, less than half the recommended winter and summer freshes were achieved. Dry conditions during 2018-19, low river flows and ash from 2019 bushfire events in the catchment all present risks to the waterway health in the Latrobe Basin3.

In the Latrobe River system there were improvements to winter baseflows in reaches with flows delivered under the environmental entitlement; however, less than half the recommended winter and summer freshes were achieved. Dry conditions during 2018-19, low river flows and ash from 2019 bushfire events in the catchment all present risks to the waterway health in the Latrobe Basin3.

Groundwater

Groundwater resources include the Moe, Denison, Rosedale, and Sale Groundwater Management Areas (GMAs).

![]() Monitoring of the GMAs indicates a long-term decline of less than 1m has occurred in the upper aquifer of the Denison GMA, and a decline of ≻2m deep confined aquifer of the Moe GMA. In the confined middle aquifer, declines were identified in the Sale and Rosedale GMAs of greater than 2m.

Monitoring of the GMAs indicates a long-term decline of less than 1m has occurred in the upper aquifer of the Denison GMA, and a decline of ≻2m deep confined aquifer of the Moe GMA. In the confined middle aquifer, declines were identified in the Sale and Rosedale GMAs of greater than 2m.

Groundwater in the lower aquifer within the Stratford GMA has declined steadily since the 1970s, at a rate of approximately 1 m/year. This is predominantly due to dewatering around the Latrobe Valley coal mines and, near the coast, offshore oil and gas extractions which are connected to the lower aquifer3.

Waterways and wetlands

441 km and 4,971 ha of riparian improvement activities were undertaken between 2000 and 2019. This included 16,367 ha weed control and 910 ha revegetation activities.

![]() The Perennial wetlands declined by 30% and seasonal wetlands declined by 19% between 1985 and 20198.

The Perennial wetlands declined by 30% and seasonal wetlands declined by 19% between 1985 and 20198.

Coast and marine

There is only a small area of mangrove cover in the local area (≺20 ha), with more extensive areas of saltmarsh (2,765 ha)8.

![]() Between 1985 and 2019 there was an increase in the area of mangroves (+13%) and an increase in saltmarsh (+5%) during the same period 8.

Between 1985 and 2019 there was an increase in the area of mangroves (+13%) and an increase in saltmarsh (+5%) during the same period 8.

The Gippsland Lakes Ramsar Site is included in the Coast and Marine Theme. The Lakes are the focus of cross-regional efforts coordinated by the Gippsland Lakes Delivery Managers, a group of operational decision makers from across the catchment.

The ecological character of the Gippsland Lakes Ramsar site is regularly assessed against the Limits of Acceptable Change (LAC) for the site. There are 20 LACs linked to the site’s Critical Components, Processes and Services. The 2020 assessment found that 12 were met, two were likely met, two were exceeded and there was insufficient data to assess four LACs10.

Exceeded LACs were for Black Bream and salinity in Lake Wellington. The LAC for waterbirds was met with the exception of Chestnut Teal.

The results for a selection of indicators are provided below:

Salinity

- Average salinity in Lake Wellington has been greater than 9.5ppt for five of the past 10 years. In 2020 it was below LAC at 8.5ppt.

LAC is exceeded.

Algal Blooms

- There have been eight algal blooms in the main lakes in the past two decades; 2001/02 to 2020/21. Several of these blooms covered more than 10% on the Lakes in the past two decades, but not in successive years.

LAC is met.

Freshwater vegetation communities

- Mapping for Sale Common indicates a difference between the wet phase in 20167 and drier conditions in 2019.

LAC is met on both occasions.- Open water – 51% in 2016 and 9% in 2020

- Native emergent vegetation – 16% in 2016 and 4.7% in 2020

- Woody vegetation – 29% at both time frames.

Brackish vegetation communities

- Mapping of vegetation at Dowd Morass was in 2015 and indicated:

- Open water – 35%

- Emergent vegetation – 29%

- Woody vegetation – 19%

- Qualitative assessments in 2018, indicated that the habitat mosaic remained.

LAC is met.

Community

The townships of Heyfield-Maffra and Sale are on a growth trajectory with populations projected to increase by around 14% between 2016 and 20362.

The natural features and proximity to the Lakes and coast act as drivers for population growth making the area attractive for sea changers. There is a dual housing market in operation, consisting both of retirees and families.

Historically the Wellington Shire Council has attracted residents relocating from the South East of Melbourne and overseas, whilst migration out of the council is typically to neighbouring local government areas11.

Current and Future Challenges

The Gippsland Lakes and Hinterland is part of a connected landscape. Threats and challenges in adjacent local areas and the East Gippsland region also have the potential to impact on the assets in this local area.

![]() Key challenges in the Gippsland Lakes and Hinterland local area include:

Key challenges in the Gippsland Lakes and Hinterland local area include:

- Water availability

- Poor water quality (salinity and nutrients

- Fragmentation of habitat

- Competition for land.

Understanding and responding to the impacts of climate change, coastal processes and associated impacts are also major challenges for agencies, private landholders, and the community.

The local area has experienced a historic sequence of fire, flood, and algal blooms and these remain prominent issues for the management of land, water, and biodiversity.

Population pressures and inappropriate visitor behaviour have been highlighted as key concerns by agency partners, particularly related to the protection of biodiversity and cultural values within the reserve system.

Changing land use and intensification of land management practices have also been highlighted as challenges, with potential impacts on soil health, water quality and remnant vegetation.

The impacts of deer and the potential increase in marine pests are emerging issues in the Gippsland Lakes and Hinterland local area.

Overview of current and future management challenges for the Gippsland Lakes and Hinterland Local Area

| KEY MANAGEMENT CHALLENGES FOR LAND, WATER, BIODIVERSITY, COAST AND MARINE | LAND | WATER | BIODIVERSITY | COAST AND MARINE | COMMUNITY CONCERNS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pest plants | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Pest animals | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Coastal erosion and coastal hazards | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Unsustainable water use/ reduced water availability | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Poor water quality (as the result of excess nutrients, sedimentation, oil spills and other pollutants) | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Soil degradation and erosion | ✔ | ✔ | |||

| Changing agricultural landuses and viability of agriculture | ✔ | ||||

| Recreational use and visitation impacts | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Salinity | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Inappropriate fire regime | ✔ | ✔ | |||

| Climate change and related extreme events (e.g. wildfire, flood, storm surge, sea-level rise). | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

Opportunities and Priorities

The Traditional Owners of this local area, the Gunaikurnai people, have cared for this Country for thousands of years. Their place-based aspirations and priorities are outlined in the Gunaikurnai Whole of Country Plan.

There are long established partnerships in this local area. The Gippsland Lakes and catchment, the Red Gum Plains and the broader Macalister Irrigation Area are a focus for agency and community action.

Management of the dynamic Gippsland Lakes Ramsar Site is complex and there are obligations to take action to maintain the site’s ecological character. Into the future change is likely to increase with an increasing population and climate change predicted to alter the system further. The Gippsland Lakes will continue to adapt to the changing conditions, and, with efforts, key values can be maintained, and new values are likely to emerge.

There is a strong commitment from agencies and the community in this local area, to continue to take a whole of landscape approach to catchment, land, and water management. Through RCS implementation there is an opportunity further explore climate adaptation options including the pathways and trade-offs that may be required to support and improve the resilience of land, water, and biodiversity.

The West Gippsland Floodplain Management Strategy analysed flood risk across the region and identified the priority actions to minimise this risk. The actions in the Strategy are regularly reviewed by the partner agencies to ensure the actions remain relevant and continue to focus on the highest priority risks to our communities.

The tables below set out the overarching Traditional Owner priorities that are relevant across all local areas and the other opportunities and priorities for agency partners and the community within this local area.

| TRADITIONAL OWNER PRIORITIES |

|---|

| ◾ Protecting cultural heritage from pressures associated recreation, land use changes and climate |

| ◾ Actively managing the water, fire, wildlife and biodiversity on Country in a culturally appropriate way |

| ◾ Having the authority to lead managing Country on behalf of the rest of the community |

| ◾ Seeking carbon production through forest restoration |

| ◾ Participating in economic opportunities, including employment and enterprise development associated with caring for Country |

| ◾ Access to water to restore customary practices, protect cultural values and uses and heal Country |

| ◾ Secure water rights to restore and reserve waterways and practice self-determination on how and where water is used for cultural, environmental or economic purposes. |

| OTHER LOCAL AREA OPPORTUNITIES AND PRIORITIES |

|---|

| ◾ Protect and improve biodiversity including through permanent protection and targeted actions to reduce threats |

| ◾ Implement actions to maintain the ecological character of the Gippsland Lakes Ramsar Site |

| ◾ Increase community awareness of the environment and provide opportunities for community participation |

| ◾ Work together to understand and implement climate change adaptation priorities at the local scale |

| ◾ Support farmers to implement practices that improve land management and increase water use efficiency |

| ◾ Support Traditional Owners’ aspirations for and participation in land, water and biodiversity management |

| ◾ Complete works to reduce risks to irrigation and urban water security and water quality (Rainbow Creek / Thomson) |

| ◾ Complete works to support the efficient and effective use of environmental water (e.g. improving fish passage) |

| ◾ Investigate and implement options to address water recovery targets (for Traditional Owner, environmental and recreational values) |

| ◾ Manage flood risks including through the use of integrated water management |

| ◾ Complete works to protect and rehabilitate waterways, wetlands and riparian areas. |

Community perspectives

What does the Gippsland Lakes and Hinterland local area look like in the future?

“All the rivers to have intact riparian zones, contributing to improved water quality and return of aquatic vegetation.”

“Think about increasing soil carbon to provide benefits for waterways, soil health and productivity.”

“Water security for domestic users, agriculture, industry and the environment. We need assurances that we will have the water whether it be for the environment or agriculture.”

“Increasing community knowledge and awareness of the environmental values on our land.”

“Better relationships between people, land and the environment, indigenous and non-indigenous people supporting each other.”

The top land, water and biodiversity management actions identified by community members were:

- Fencing of waterways and native vegetation

- Provide environmental flows and associated infrastructure to support waterway health.

The top areas of focus for climate change adaptation were:

- Maintain a diversity of habitats, environments and species to maximise the chance of survival

- Increase carbon sequestration through activities such as revegetation and soil improvement

- Improved agricultural practices and positive landuse change to ensure enterprises remain viable

- Incorporate climate change projections in landuse planning and development.

The top areas for helping communities and industries to participate in land, water and biodiversity management were:

- Collaboration between agencies and community/industry on projects at a local level

- Grants or incentives to undertake projects

- Information/advice to improve knowledge.

“All we really need is more money to do the work, not more reports. We need to take action not just write reports, without money we go nowhere.”

“We need to be imaginative and think of innovative options and improve the attitude towards the region. We don’t want the Latrobe to be the dirtiest river in the region.”

Management Directions and Regional Outcomes

Management directions are the overarching strategies to guide agency and community collaboration. The agency and community priorities outlined above will help to realise the management directions at the local area scale.

Implementation will be guided by regular Local Area partnership forums and implementation planning processes that prioritise effort with consideration to value for money, and issues of feasibility and risk.

Priority management directions have been defined for each theme: Land, Water, Biodiversity, Coastal and Marine, Traditional Owners, Community and Climate Change.

The RCS outcomes hierarchy can be found here with a more detailed matrix showing how the medium term outcomes align to local areas here.

Further details on RCS implementation can be found here.

References

- WGCMA. Lake Wellington Land and Water Management Plan. Traralgon : West Gippsland Catchment Management Authority, 2019

- RMCG. West Gippsland Regional Catchment Strategy Review and Renewal Report. Prepared by RMCG for the West Gippsland Catchment Management Authority, 2020

- DELWP. Long Term Water Resource Assessment for Southern Victoria. Basin by Basin Results. East Melbourne: Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning, 2020

- WGCMA. West Gippsland Regional Catchment Strategy 2013-2019. Traralgon : West Gippsland Catchment Management Authority, 2013

- WGCMA. West Gippsland Soil Erosion Management Plan. West Gippsland Catchment Management Authority, 2008

- DELWP. Biodiversity Response Planning Fact Sheets. Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning. [Online] 2021

- Van Dijk, A and Summers, David. Australia’s Environment Explorer, The Australian National University. Exposed Soil. [Online] 27 November 2020

- DELWP. Victorian Land Cover Time Series Data 1985 – 2019. East Melbourne : Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning, 2020a

- DAWE. Collaborative Australian Protected Areas Database (CAPAD) – Terrestrial & Marine. [Spatial Layer] Canberra: Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment, 2021

- EGCMA. Gippsland Lakes Ramsar Site. Ramsar Site Management System. Final Assessment against LACs. East Gippsland Catchment Management Authority, 2020

- id. Drivers of population change – Wellington Shire Council . [Online] January 2021

- ABS. Agricultural Census: Agricultural Data – 2005-06, 2010-11 and 2015-16. Canberra : Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2020

- WGCMA. West Gippsland Waterway Strategy 2014-22. Traralgon: West Gippsland Catchment Management Authority, 2014

- DELWP. Biodiversity Response Planning fact sheets. Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning, 2020

- CES. Victoria: State of the Environment 2013. Melbourne : Commissioner for Environmental Sustainability Victoria, 2013

- DELWP. Draft Gippsland Regional Adaptation Strategy. Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning, n.d

- MACC. Protecting Traditional Owner Country of the Gippsland Lakes. Gunaikurnai Land and Waters Aboriginal Corporation. [Online] November 2020. Victorian Marine and Coastal Council, 2020.